By Philip Cauchi

Question - I notice a lot of pro teams are now playing with a back three. What are the pros and cons of a back three?

Playing with a back three comes down to the quality of players you have in your team. If you don’t have any natural wingers then you might need to change the formation around in order to still have balance in the team. This might require the use of wing backs who will be positioned in line with the midfielders. The wing backs venture up and down the flanks while adding another player at the back. Therefore having three central defenders instead of two. We might even have one of the central defenders who is confident in moving into midfield, thus creating an overload in this sector of the pitch.

A natural strength of playing with a back three is creating a numerical overload when playing against formations with two strikers. Threats are further limited if playing against systems with no wingers such as the 1-4-4-2 with a midfield diamond, and the 1-5-3-2. Against these formations the possibility of getting outnumbered on the flanks is reduced. However, during the finalisation phase of the build-up we rely heavily on the quality of our wing backs especially in 1v1 situations (qualitative superiority), in order to create the necessary width and get past opponents from the flanks.

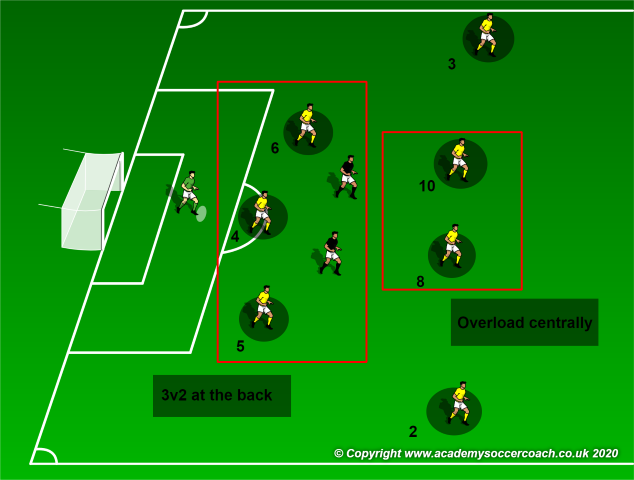

Figure 1 –Creating overloads in crucial zones with the aid of the two midfielders shielding the back three.

Another factor which I consider to be a strength is that if the opponents are playing with a single striker, we can advance one of the central defenders into midfield during the possession phase and create a numerical overload as already mentioned in the first paragraph. Furthermore, with three central defenders we will be able to cover the central zone better.

A major weakness when playing with three at the back would be that we will lack width at the back and thus constantly require the support of the wingbacks to drop to retain defensive balance. This becomes even a bigger problem if the opponents play with three forwards and therefore be in a numerical equality at the back. If the opponents also have qualitative superiority we would be forced to lower the position of our wing backs which will reduce our effectiveness in attack as we will have less players forward and thus possess less options to play in verticality (limited penetration).

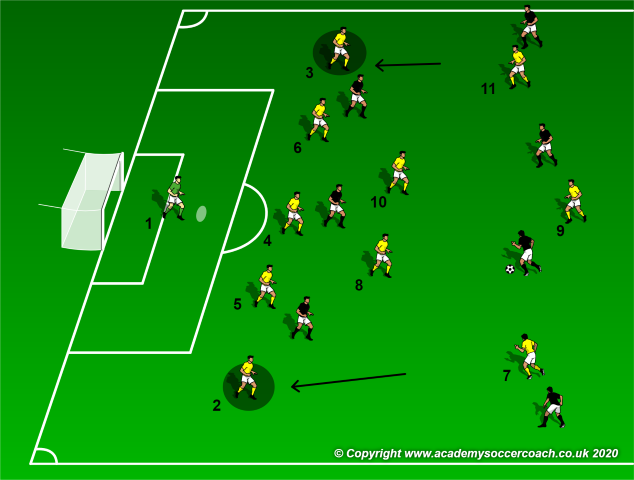

Figure 2 - The wing backs will need to drop to cover the spaces on the flanks and also prevent that the closest central defender will be pulled out of position or getting outnumbered.

The wing backs play a crucial role when defending flank attacks. If the wing back on the side of the attack doesn’t drop to engage the opponents, the central defender on that side would be required to come out and apply pressure on the ball. The other two central defenders will be forced to shift in order to cover the central area. This movement makes us vulnerable for attacks on the weak side with a quick switch of play. To counter this we will require that the opposite side’s wing back drops to restore defensive balance. If this player fails to recover on time, the central defensive midfielder should immediately insert him/herself into the back line.

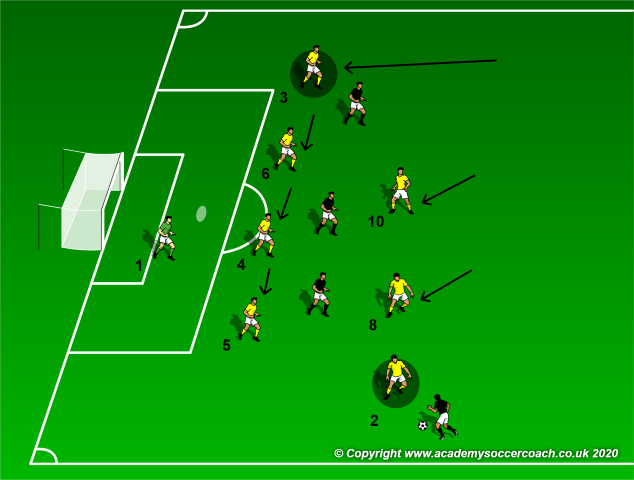

Figure 3 - The ball-side wing back (number 2) is engaged in a 1v1 duel while the opposite wing back (number 3) inserts himself in the back line to help retain defensive balance as the rest of the defence has shifted across.

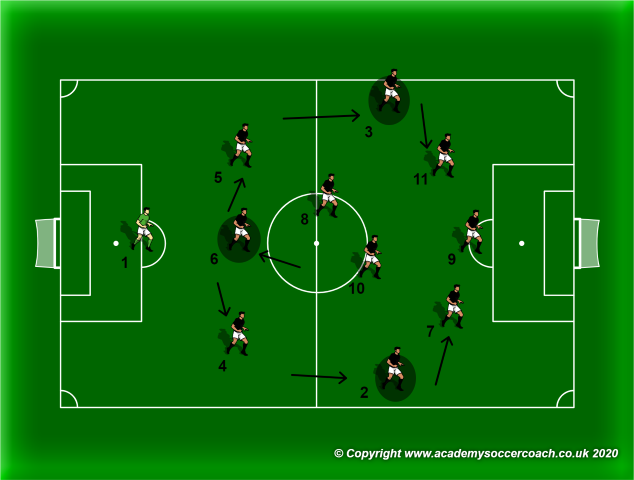

Many teams nowadays play with a system operating four at the back. However, what they actually do is that in the phase of possession and especially if they are in possession in the attacking third of the pitch, they push both full backs forward to have width, while dropping the central defensive midfielder in line with the two central defenders, thus creating three at the back. It can also be that one of the full backs attacks as he/she is more offensive while the other stays back to retain compactness. In the defensive phase the same team might have five at the back to cover better the width and deny the opponents to outnumber them anywhere at the back. The central defensive midfielder normally drops to help create a further overload in the middle and prevent situations of numerical disadvantage in such a critical sector of the field.

Figure 4 - The central defensive midfielder or the low lying playmaker (number 6) drops between the central defenders while the full backs 2 and 3 push up the flanks to occupy the spaces vacated by wingers 7 and 11 respectively who have move towards the inside.

Top level teams have players who possess a high level of tactical intelligence. They themselves can easily adjust whether to remain three at the back, or even two if their technical level and the situation on the pitch permits this. These players can also adjust their position to retain team structural balance in the phase of non-possession.

By Philip Cauchi