RESEARCH: Projecting the intensity of the session based on HR, Perceived Exertion and Global Position Systems.

A recent study in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research ((Gomez-Piriz, Jimenez-Reyes, & Ruiz-Ruiz, 2011) looked at a possible way to rate the intensity of a training session using various means of global positioning systems (GPS), heart rate (HR) and rate perceived exertion (RPE). The authors stated research that validated the use of HR and RPE as accurate predictors of session intensity, but wanted to examine the use of total body load (TBL), collected by measuring acceleration forces (walking, acceleration, deceleration, change of direction, tackling, etc.) during small sided games.

The authors quoted another study (Reily & Bowen, 1984) that mentioned how, “…unorthodox modes of motion such as running backwards and sideways and changing direction accentuate the metabolic loading” and therefore might through off the RPE. They also mentioned studies that determined higher RPE and blood lactate when working with a ball. The authors concluded that using this type of GPS is great for looking at the types of movement, but might not accurately depict the session intensity as well as HR and RPE.

When players are moving in tighter spaces or forced to react quickly to a changing environment (as in drills that involve a ball), the muscular demand is much higher due to the quick starts and stops, repositioning and reacting that is required. To drive this point home try chopping your feet as fast as possible for 10 seconds. Your heart rate will raise and your legs will begin to feel heavy. Now run in a straight line for 10 seconds. Your heart rate will not go up as high, and your legs will not likely feel the same type of fatigue. But as far as GPS is concerned you will have covered more ground, therefore making the bout more intense.

We notice this all the time with our players. Our agility sessions (especially those done with a ball) seem to drive up HR and RPE much higher than those conditioning sessions done in more linear fashion without a ball, but we tend to lose the overall fitness demand we might be looking for out of the session. For example our Soccer FITness Interval can be done with and without a ball, and although there is a technical efficiency component to this drill, we still find players will fatigue, on average, 45%-65% faster with a ball even though their skill deficit might only be 10%-15% lower and the pattern of runs is exactly the same.

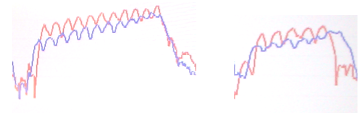

The HR graph below is from our SoccerFITness Interval where two players with excellent fitness and technical skill were able to last for 11 intervals (180 yds per interval with 30 seconds recover) without a ball. When the ball was added, HR did not get as high, but due to the increased demand with the ball, the players were only able to last 5 & 6 intervals. RPE at the end of the interval with the ball was at a 10 on a scale of 1-10 on both.

If we were just looking at distance covered we might think that the session was less intense when the ball was added. But based on RPE, we know that the intensity of the sessions were identical. If we were only looking for fitness we might want to choose the interval without the ball, as we were able to last longer and achieve a higher cardiovascular workload.

The take home point of all this is to know what you are looking for in a fitness session. If you are looking for HR response and enhanced aerobic capacity, working with a ball might not be your best choice. However, as we found out in a session last week. Combining small sided games and fitness intervals gave us the ultimate mix of Game Speed Fitness – Soccer Skills, Player Communication, HR Response, Agility and Fitness.

This particular session, which I will highlight in a future post with video and HR graphs, was built around 2v2 sessions in a 12 x 25 yd grid. Each bout lasted 2 minutes and was immediately followed by the winning team running ½ of a stage of our Soccer FITness Interval or 90 yds with 5 changes of direction (sprint down 10yds and back twice and then sprint down 25 yds and back once – players must be back in 22 seconds). The losing team ran two of these (180 yds). Then after a 1-minute rest, play resumed in the 2v2 small-sided games.

By the 30th minute, technical skill was diminishing so I cut the interval runs in between the 2v2 bouts. After the session, several of my U14 players came up to me and asked why we cut the interval runs. They commented that they needed the additional fitness, and they felt like the session didn’t end as strong as they had hoped. This just goes to show that my players were looking for FITNESS and they felt they were getting it in the integrated approach. But when we simply rely on the game, the fitness aspect dropped off significantly.

Know what you want from a session and stick to the plan, it will work.

1. Gomez-Piriz, P.T., Jimenez-Reyes, P., & Ruiz-Ruiz, C. (2011). Relation between total body load and session rating of perceived exertion in professional soccer players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 25(8), 2100-2103.

2. Reilly, T and Bowen, T. (1984) Exertional cost of changes in direction modes of running. Percept Mot Skill 58, 149-150

3. Reilly, T and Ball, D. (1984) The net physiological cost of dribbling a soccer ball. Res Q Exerc Sport 55, 267-271

Scott Moody acts as the director of the SoccerFIT Academy in Overland Park, KS and has spent the last 10 years developing a curriculum that bridges the gap between the physical and the technical developmental aspects of soccer. His website, www.soccerfitacademy.com is designed to be an educational site that promotes discussion, offers ideas and breaks down current trends in research and training to offer suggestions as to how it can be applied to youth player development. Scott also is a featured speaker, author and research fellow for numerous organizations, equipment manufacturers and online training magazines.